As I drove home from the party where I had met the two young attorneys and asked my more elderly friends whether they would choose to live for 200 years in a young body, I found myself reaching back into literature for examples. If we try to imagine what it would be like to be forever young, the Greek gods leap to mind. They have power, beauty, strength, and everlasting good looks, and mostly they get to do whatever they want. What’s not to like? Indeed, the gods seem to have much in common with the paragons of success we have just mentioned—the movie stars, tycoons, and generalissimos propped up by makeovers, money, and medals—except that to them it comes naturally rather than by effort and design. The gods have it all. And they don’t even have to work for it. Plus, they’re immortal. Who wouldn’t want to be just like them?

But this picture loses some luster when we look more closely at the actual life of the gods. Certainly they don’t lack for drama; they’re deeply involved in human life with all its passion and intrigue. But oddly, they don’t seem to learn anything from their experiences; they just keep doing the same things over and over. Zeus keeps seducing nymphs and mortals, getting them pregnant and then vanishing into the ether; he never matures into fatherhood, as if he were stuck in late adolescence—not unlike the tycoon with the sports car. Ares can’t stop waging war; he’s an old soldier who never dies but can’t fade away. Aphrodite can’t stop primping and having affairs, a Miss Havisham who never loses her looks (think how scary that would be!). Nothing that happens ever seems to register with the gods; you would think they’d get bored. And what is worse, they seem overly dependent on the adulation and rites of their worshippers, as if they needed constant reassurance.

Perpetual youth begins to look even less attractive when we fast forward to the Christian era. In Dante’s Inferno we meet Paolo and Francesca, the murdered lovers whirled and battered by the hurricane of their deathless passion. They still have their looks and their love; they have each other. But they’re not having fun: they’re just going around in circles, suffering without learning. They can’t escape each other—hell, they don’t even talk to each other. Francesca ignores Paolo completely while spinning a heart-wrenching, self-serving tale of glamor, romance, and betrayal. Her attention is fixed on Date and Virgil. As for Paolo, all he can do is weep. This does not look like a very fulfilling relationship. Like everyone else in Hell, Paolo and Francesca are living in the past, obsessed with their earthly life and careers. Francesca talks and acts like a princess out of chivalric romance, idolized and irresistible, an icon of feminine charm. It’s this power that she worships, explaining to Dante that Love is an irresistible force that compels any one loved to love in return. She’s in love with Love, instead of with God. “It wasn’t our fault,” she complains. “Love made us do it. Why should we suffer for how we were made?” But the creepy thing about Francesca is that she doesn’t want to give up this adolescent feeling of power; she doesn’t want to grow out of it; she doesn’t believe there could be anything better. She can’t imagine—doesn’t want to imagine— what it might be like to be Beatrice.

As Dante and Virgil go deeper into Hell, they meet more and more people who are still obsessed with their careers. Farinata, a famous general and statesman damned for denying the immortality of the soul, only wants to know Dante’s ancestry and party affiliation, as if these mattered any more; if he had any sense, he’d ask Dante what he’s doing in Hell, and whether he can help him get out—especially given the fact that he, Farinata, is burning, in blatant refutation of his earlier beliefs. But like everyone else in Hell, he doesn’t learn from experience. It’s the same for Brunetto Latini, Dante’s old professor, who’s amazed to see his ex-pupil favored with a guided tour but attributes it to political talent rather than divine grace. He, too, doesn’t ask for release, but instead urges Dante to remember his book—as if, given the circumstances, that would be a reliable guide to truth!

It isn’t until Dante gets to Purgatory that he meets people who have moved on from worldly accomplishment to embrace the challenge of spiritual growth. And what a change it is! People don’t want to dwell on the past but instead on the climb ahead; kings and rulers who might have waged war now comfort and encourage each other; Oderisi, famous for his illuminations, now cedes the future to painting and the glory to Giotto. Instead of claustrophobic darkness and torments we have clean air and sweeping views, with sunshine by day, starlight by night, and loving companions all the way. What could be better?

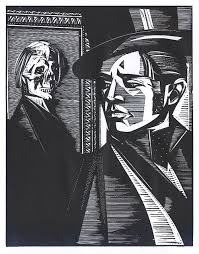

Moving toward our own day, whose worship of youth and vigor provide countless opportunities for decadence, we encounter Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde’s famous antihero who retains his youthful good looks even as his portrait grows older and uglier. Dorian soon discovers this miracle, but, rather than learn from it, he decides to exploit it. He hides the portrait away while using his charm for power and pleasure. A friend introduces him to J.K. Huysmans’ sensational novel À Rebours (“Against Nature”), whose wealthy protagonist embarks on a quest to explore every sensory pleasure while sequestered in his artfully engineered estate. Dorian takes that as his bible and before long has outdone its hero, Des Esseintes, in both depravity and excess. As the noose tightens around him, Dorian begins to hate the portrait, which exposes his true self. Fearful that it might be discovered, he decides to destroy it, but when he slashes it, he mortally wounds himself.

These examples all show the danger of not moving on, which amounts to a kind of self-seduction. For youth is something to live through, not to cling to. It gives us strengths and opportunities to use for growth, not to clutch in despair. Learning of any kind depends on relinquishment; the new knowledge and understanding have to displace the old. For scholars this may be bitter medicine. We all hope that our work will last. But doesn’t the ongoing conversation of scholarship depend on both our work and our careers becoming obsolete?